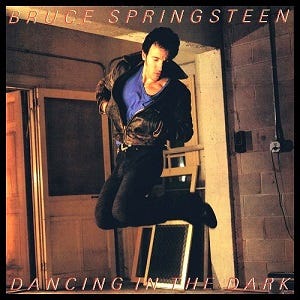

The grasping one does in their youth—for hope, for purpose, for strength, for a warm body to envelop with handsy desire—is never more truthfully crystallized than in Bruce Springsteen’s earlier work, and for me, in the 1984 song “Dancing in the Dark” (hereafter DITD). Yet without the luxury of space provided by a novel or movie, Springsteen encapsulates so much of the distress of youth in four minutes.

This song is, by 2019 standards, not a cool song. It introduces itself to you with a keyboard, and it salutes you goodbye with a sax solo, both carrying a mood of Buddy from the Dive Bar who Wears a Look of Withered Optimism that His Day is Gonna Come Soon, Johnny.

Well, the dive bar was recently turned into a sushi fusion spot, so Buddy has to drive ten minutes further for his Miller Lites now.

It has a matter-of-fact drumbeat keeping the rhythm, and a middle of the road tempo that feels distinctive of the past, now that songs written today are either hyperized beats to forget about your problems, or indica-inspired fugues to deliberate on your problems. DITD is a brisk walk with the Bard of New Jersey telling you “these are my worries, and I know they’re your worries, too. Why else would you agree to take this walk with me?”

This all may seem like an overreaching exploration of a song that, on first listens, seem to be primarily about horniness (if you’re under 22 and reading this, this is the emotion we used to call thirst, which despite its zeitgeisty ephemeral, I prefer because the word thirst is so much better than one of the Top Five Worst Words©, horny). But to argue that this song is about getting your rocks off with any willing participant is to overlook codependent facets of youth; that the loneliness and the ugh, fine, horniness are two sides of the same coin. The lust is a ligament that extends from the need for connection, for understanding, for a wool blanket over our soggy shoulders at the end of a very, very long day. And this man knows long days. I get up in the evening, and I ain’t got nothing to say. Each day runs together because they’re not worth separating.

You may also hear this song and hear a hustler’s anthem, a greased-up guy (be it from vocation, since we know thirty percent of the protagonists in Springsteen songs are mechanics, or aesthetic, because maybe Buddy’s slicker cousin Johnny likes the feeling of running pomade through his hair, which don’t hurt nobody, duzit?) telling you that you can’t start a fire without a spark. Just give me one look. Accept my offer, this gun’s for hire, we’ll both be free, if only for a night. It feels like I’ve been fishing for so long that the bait swam off with the fish.

Has the sky ever not been gray? Don’t you need to get out of this, too? Your world won’t soften if you keep crying about it. Your sky won’t turn blue without changing things, without taking a chance. And here I am, motor running.

The fact is, greased-up guys want to feel connection and of use like anyone else, if not more so. Our man is willing to put the laugh on me, to hold your hand towards a lighter feeling, even though he’s just about starving tonight. He’s telling you he needs a little help, to the extent that he’s euphemizing so hard he says he needs a love reaction. That being said, the protagonist has an overlooked wisdom, because he knows that the woman he’s talking to – and maybe it’s a new one every night, God bless him for trying – needs to look up from her pain and try to have a little fun. The wound can heal when the dancing begins. The tears would dry if you’d just take a drive with me. No pressure, no expectations, no binds, just a glint of hope. What harm is there in dancing in the dark? Don’t we need to forget the burdens we shoulder as much as we need to breathe?

Prose about quotidian life is one of the most affecting subgenres, and that’s why our so-called ordinary thoughts and feelings are continual inspiration for arts of all expressions. The most evocative stanza of a poem, scene in a film, line in a song is two meek hands entwined, watching the girl walk away down a crowded street, an old man’s knowing smile. Springsteen’s catalog is comprised of these small moments that are the patchwork of a man’s life, a life that may seem small as you drive by that man’s house but feels big when you hear him singing about his pain, his longing, his hope in abstentia. Of all his songs, DITD is the tapestry my eyes see most vividly, because the knitting is so intricate but the rug is so worn.

And this song speaks to me on an arterial level because the protagonist is insecure, tired, and looking to escape the prison of the self. Aching for someone, anyone, a gun for hire to combine our energy with, so as to forget our own singular existence and what we don’t just dislike, but loathe about ourselves. Want to change my clothes, my hair, my face. Maybe the kindest thing we could do for an adolescent we know is show them a photo of Springsteen, hounded by the sweaty adoration of fans, and play them this song. You can change your life. You can be adored, and they will come in droves. You won’t even have to fight for it.

Except that, of course you will have to fight for it. It’s all about the struggle; it’s always been about the struggle, and the hopeful winding road to exultation. It’s what Tom Hanks’ Jimmy Dugan says about baseball in A League of Their Own: “the hard is what makes it great.” Springsteen’s path to adoration was singing about the dampest, puniest parts of ourselves. Always grasping, hands calloused from grasping. At a chance, at a steering wheel, at a plain Jane except her name isn’t Jane, it’s Mary or Rosie or Peggy or y’know what, it could be Janie. It could be anyone, if you’ll let me be your hired gun? I’m dying for some action.

Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band was my first concert, at Madison Square Garden when I was seven. I liked it because it was exciting to be at a concert but had little interest because my parents took me. Even at a young age, I knew that my parents liking something wasn’t cool. A score later, after much indoctrination through car stereos, increased emotional intelligence, and frankly, being from New Jersey, my tune has changed. Soon after I moved to Los Angeles from New York last year (a wholly unique voyage, I know), I found myself playing Sirius XM’s E Street Radio (Channel 20) almost every time I was driving. And as I was on the Hollywood Freeway one morning, green hills stoic in front of me, grimy, shiny Hollywood to my left, I realized why. This audio security blanket nestled me as I braved a commute I was navigating, a job I was learning, a place I was acclimatizing to that was sprawling and somewhat inhospitable. I learned new, but really old, Springsteen songs I hadn’t taken the time to listen to, and like a dolphin’s sonar, my ears tracked down a relic of familiarity. I found the beating heart of my fears and doubts echoed back to me from four decades ago, reminding me that I’m one in an army of many just tired and bored of myself.

I accept that it may be dreary to dive into an existential coral reef of this song over others in his oeuvre, given its pep, its confidence, its glorious Courteney Cox dance moves in the Brian De Palma music video. Even its external track record, of being the highest charting single of Springsteen, his most played on Spotify, and the only platinum single of his career, could be quantifiable proof of the magic of this song, but I hem and haw over even mentioning this, because critical acclaim and monetary success is irrelevant to this exercise. Besides, this isn’t even my favorite Springsteen song. But it is the one that reverberates, most deeply and most unexpectedly, into my soul when I hear it.

His generosity to the woman fretting in front of him, worrying about your little world falling apart, trying to cheer her up and assuage her sadness, is remarkable. And it is self-serving, because if she’s blue, she won’t join him – in revelry, in movement, in literally dancing in the dark, in sex, both, neither. The world has asked so much of him, but he’s not asking so much from her. Even if we’re just dancing in the dark. Even if we’re just dancing in the dark. Even if we’re just dancing in the dark.

The respite Springsteen speaks of is one that everyone, but particularly young people, search for in myriad ways: drugs, alcohol, sex, clubbing, dancing, even fucking reading, whatever gets you an inch closer to oblivion. But this man knows, whether through previous trials or because he’s more observant or because he has so little to lose, he knows that the sincerest oblivion is losing yourself in the arms of someone else.